i

Roy Grimes disagrees with his mother and their disagreement is within the tradition of what might be called black disbelief. Black disbelief, it seems, is a refusal of the conditions of one’s life worlds while simultaneously enunciating the possibility for something new, something otherwise. Roy Grimes, in Go Tell it On the Mountain by James Baldwin, laments to his mother Elizabeth, saying that the actions of his father Gabriel do not meet up with the rhetoric of holiness and righteousness, that the violence and violation Roy receives is not consistent with the ideology and religiousness of a love ethic that is pronounced verbally. Within this gap – of which the London Underground Tube system tells us to “mind” – is the radical force of love, its capacity to produce otherwise worlds that are not grounded in such violence and violation. Roy’s is an ethical charge against the normative modes of his existence: he disbelieves that violence is concomitant with love, he disbelieves that physical, emotional and spiritual abuse is a mode of protection. He does not want to be a citizen of the household of faith, nor of Gabriel Grimes’s domestic space, because with such citizenship comes the relinquishment of liberatory praxis, of living vibrantly and abundantly. With such citizenship comes duty and obligation but certainly nothing like joy or peace. Roy, it seems, recognized this all. Roy’s frustration and demand, his disbelief, emerged from his acute perception attuned to the ways that he is victim of inequitable distributions of power. But his being victim was not a totalizing force, so much so that he spoke back, forcefully, truth to power.Nina Simone corroborates Roy’s charge. At the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1976, Nina Simone produced a rendition of the song “Feelings” by Louis Gasté and Morris Albert.

What strikes me each time I listen is her interrupting the song almost at its very beginning to say, “What a shame to have to write a song like that,” of which she quickly followed with, “I’m not making fun of the man. I do not believe the conditions that produced a situation that demanded a song like that!” She looked on, after having offered such commentary, to the incredulity of the audience. They could not comprehend her disbelief in the very situation from which a song emerges. Their refusal of comprehension was an articulation of the privilege that disallowed engagement, incarnation, fleshliness in our world. Their refusal was a mode of rapture, leaving behind those who disbelieve as a material spiritual practice.Roy Grimes is our guiding post. His desire and demand for love is an ethical injunction against not only the conditions of his world but ours as well. He did not speak merely of a mode of affection that is ephemeral in its enactment. He spoke of a love that charges his parents to live into the world differently, to ethically engage their children through reciprocity and concern, through the obliteration of hierarchies that are grounded in unjust power differentials. He desired a love, in other words, that fundamentally would alter the alienation produced through violence, he desired a love, in other words, that would, in sociality, flower. Simone pinpointed the very thing Roy lamented, she elucidated a black disbelief: that there are situations that produce demands on and for us to speak, demands that have ethical force and thrust. We live in such situations, such moments of crises.

And so we listen and incline our ear towards Roy’s lament, towards Roy’s critique of violence and violation. We sit still with Roy, hearkening to his disbelief, making it our own,

ii

We live in a world of namings and misnamings: arguments over if someone is or isn’t a “public intellectual” (Melissa Harris-Perry, for example); if someone is “dumb” and “stupid” (Porsha Williams of Real Housewives of Atlanta fame, for example); what “affordable” in terms of housing means; “urban renewal” in terms of gentrification; “choice” and “charter” in terms of privatizing and defunding equitable educational schooling opportunities for young folks. What these modes of naming do is provide a monolingual reduction of words, they oversimplify the complexity of life experiences. There is an assumption that the words have within themselves crystalized and concretized meaning, that they have self-evident capacities to name realities. But what seems apparent in our pernicious times is how these words often disallow rigorous analysis in the service of ease and comfort with our political ideologies. Let’s consider Barack Obama as a primary figuration of such misnaming.

Barack Obama – so the various opinions claim – is “smart” particularly over and against the “dumbness” of his predecessor George W. Bush. His being “intellectual,” his reading books and newspapers and his being a “constitutional scholar,” are all facts mobilized to underscore just how smart he is. Yet, these words merely oversimplify the pervasiveness of violence that has proliferated under his administration. Smartness, intelligence and intellectuality are instrumentalized to shield from a fundamental truth: Obama’s tenure as the leader of this supposedly free world has been more radically violent, economically inequitable, more secretive and surveilling than anything the “dumb” Bush could have imagined. Misnaming produces the conditions whereby we can avert gazes from the violence produced and, instead, celebrate symbolism. When the words are mobilized to veil from the fact that the actions they obscure enunciate quotidian violence, the urgency of minding the gap, of Roy’s ethical injunction, intensifies. It’s all about the words used and how they cohere with or against actions.The crisis occurring in American urban cities – through privatization of schooling, gentrification, displacement of communities, joblessness and chronic unemployment – is called urban renewal. What sounds like a solution ends up being a perpetuation of the cycles of inequities, a proliferation of systemic and institutional violence.Barack Obama has, for example, recently named five “Promise Zones“: “the President’s plan to create a better bargain for the middle-class by partnering with local communities and businesses to create jobs, increase economic security, expand educational opportunities, increase access to quality, affordable housing and improve public safety.”

However, the Promise Zone is just a misnaming, an other naming, of what came before under previous administrations as “Empowerment Zones” and “Enterprise Zones” (Reagan and Clinton as examples). With these purported “promises“ are a bootstrap-like mentality, the people whose necks are under the boot of empire are the ones required to make a promise to empire, to better citizens for its goals and purposes. But so far, we on the left have raised little voice against such violent policies that leave the structures producing inequity intact. Though we’ve written lots about Beyoncé’s feminism and Ani DiFranco’s plantation blues and (the quite terrible) Macklemore’s win of four Grammy’s, much less has been said from our circles about the cycles of violence and violation. There is a gap, of which we are not minding, between the profession of faith in social justice and that which rouses us to collective outcry and action. Or, more precisely, the actions which we engage often are in the service of articulating the personal, private individual, the enlightened bourgeois subject, through acts of personal, private social piety.

iii

Some of us took it to the walls, paint on rollers and got to work, making old t-shirts a bit dirty, meeting folks along the way. Others of us, perhaps, donned tool belts, put nails in drywall and through wood. Some of us went to food banks, placing rice in bags for a few hours. This is what has become of the day to remember Martin Luther King, Jr., plain ole personal good feelings. The day to remember King has been co-opted by the government since 1994, officially called a “Day of Service.”

And there is something pernicious about the exchange of the seeming immemorial death and remembrance of Martin Luther King, Jr. with volunteer work, replacing the radical force and ethical charge of King’s black disbelief against the conditions of the world from the political zone of dissent against empire with projects that consume our time, replacing the affective labor of black radicalism with the ways to feel self-satisfied about a “job well done” through service projects. We live in a moment of aversion. What was engaged that day were projects grounded in a logics of aversion, projects that take our energies away from considering the conditions that produced King’s assassination. Through “service,” our attention was diverted towards rearticulating the personal, private individual as most in need of development. The personal, private individual is the one who volunteers, who does projects, who addresses needs of communities mired in poverty, inequity in education and victims of food insecurity. All the various well meaning projects can make us a little bit exhausted, can introduce us to various folks we’ve never met, and can allow us, at day’s end, to be self-satisfied. These projects let us gather around a concept called volunteerism with hopes that such a concept will have within the power to rename our realities. It is a misnaming steeped in a belief in the power of words themselves to do the work of justice.

What are you doing on Martin Luther King’s birthday?I’m volunteering!

What got King assassinated, however, was not a simplistic notion of service, was not the articulation of a political subject of the state as most in need of protection. King was not assassinated, in other words, because of the notion that his identity as a black man was a particularly unique and individuating mode of victimhood. Rather, his murder emerged from his recognition of the fact that until we attempt to unsettle and uproot systemic structures of inequity, that we simply participate in the perpetuation of American exceptionalism. He spoke out – finally – not just against racism, but also against warfare and American militarism and, also against poverty. King, like Baldwin’s Roy, began to mind the gap between the rhetoric of the “greatest nation” and the forms of violence it produces globally. King became aware of the ways empire itself produces inequity at home and any abroad. And the tactic of American empire has been to mute his radicality and critique, to appease us with feel-good service projects, such that we think Barack Obama is a logical extension, rather than an vulgarization, of King’s life struggles. Simply, the word “service” has come to replace justice work, the act of personal volunteeristic piety has come to replace the hard labors of struggling against empire.

This misnaming is not unique to King and a “Day of Service.” This misnaming, this oversimplification of words, is what has allowed the ongoing opening of Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp that has detainees whom have never been charged with any crime at all, detainees who have been cleared for release. This oversimplification of words is what has the Affordable Care Act touted to be “universal” healthcare rather than, say, single-payer health insurance, which would, not just in rhetoric but also practice, be “universal.” These various misnamings are made possible through the logics of aversion, through a turning and turning away from the injustices right in front of us, turning and turning away with hopes that naming will otherwise do the work of justice.King’s was a critical intervention grounded in the spiritual practice and exercise of black disbelief, not in some sort of secularity that was about becoming a political subject of the state, about becoming a proper citizen. Misnaming is a problem of the secularizing – having an aversion for certain forms of social practice – of our society. Secularizing makes certain concepts available universally through a liquidation of the radicalized potential and force, leaving unchanged the inequity that produces the desire for secular civil society. What we have, then, is a secularized King, a defanged and muted object, no longer produced by and producing black disbelief as an antagonistic way of life, but now an object of suffering that is merely exchangeable. Though King was certainly about serving others, what is meant and produced by the “Day of Service” and making a political claim on his service is that King becomes a politically coherent object that serves the interests of empire, he becomes a symbol in empire’s hands and, thus, exploitative powers.Such that there is not much difference between the promotional flyers of Martin Luther King, Jr. celebration parties and the calls for service work in his name. The flyers simply makes explicit the objectification that undergirds the latter, while at the same time, the latter comes with it a moralizing stance and operates in the service of empire building.

iv

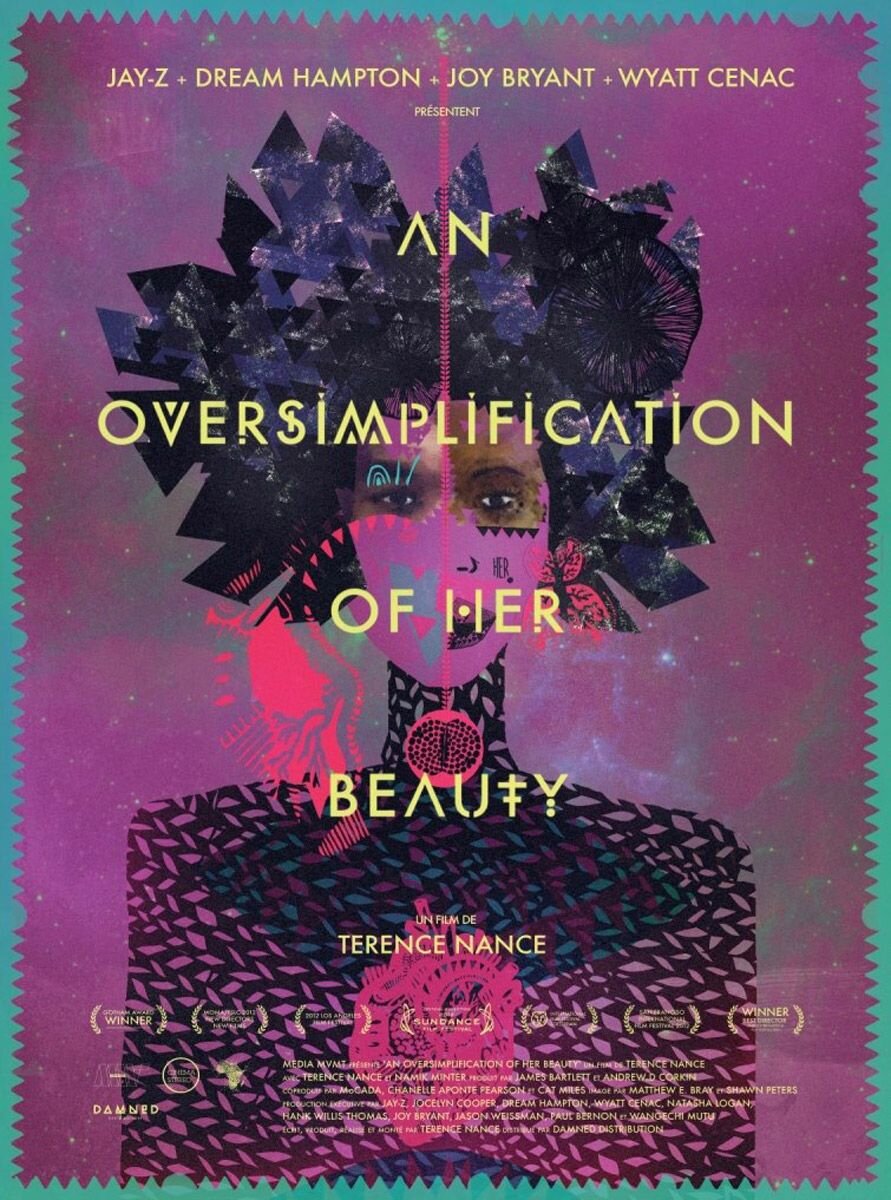

An Oversimplification of Her Beauty is a sumptuous, gorgeous, moving film. A complex set of images, An Oversimplification of Her Beauty is about the possibilities for love, for thinking about and experiencing emotions when there is complexity built into, but unspoken within, relationships. An Oversimplification of Her Beauty begins with the tale of an artist who is one night stood up by a would be lover friend and the varied feelings he has for her. This beginning is announced in a film titled How Would You Feel. But immediately as this first film begins, it is interrupted by another film, An Oversimplification of Her Beauty as that interruptive force, to give context, to give flesh and meaning to what is in the first, original film. So with How Would You Feel, viewers gain an entry into the psychology of the filmmaker and his feelings about “her.” In An Oversimplification of Her Beauty, viewers gain an understanding of “him,” his previous relationships, his complexities. This collection of films is about black disbelief, refusing the conditions of the single narrative to tell the story, displacing the single author, the single medium, the single voice in order to have various voices, textures, colors, media types to present a set of interconnected stories.

And through the film, we come to learn that oversimplification seeks to make rational the feeling of beauty. Feeling itself, it seems, is something in need of control. Oversimplification is the reduction of excess, the discarding of the not easily named emotional registers of inhabiting the world. Oversimplification is fundamentally a secularizing of the object of our affections. But the two films – each interrupting the other – move through several narrative voices in blurry places, in the middle of passages, in the middle of words; it is sometimes animated, sometimes live-action, sometimes puppetry; it is repetitious while also varying themes with each repetitious return. As such, the film seeks to unsettle such secularity by celebrating the excess of performance and form: everything from voice to artistic visual representation, from documentary to fictional presentation, all to get at something about “her” beauty, the beauty she has that augments and interrupts him.

The film is a critical intervention into, and an interruption of, oversimplification of words, of sentiments. It refuses singular form in order to trouble linear narrativity. It is an ethical film, a film about the gap between words and actions, the zone of the oversimplified. But the film speaks back from that zone to say those that have been oversimplified are anything but simple. When “her” finally speaks, she speaks with depth, with care, with precision, with love. She, a character of black disbelief, speaks against the ease with which she is narrated in How Would You Feel as simplistic. She interrupts the ease with which she is misrepresented, the ease with which she is turned into an object of his suffering for exchange in the film.

I have been bothered by the concept and theological idea of rapture for some time but it seems to structure the ways in which we inhabit our western world. Rapture is about escaping the conditions of suffering “when the trump shall sound” with folks leaving the “unsaved” behind to live in a world of crisis. The concept of rapture, it seems, is fundamentally about escaping conditions rather than inhabiting them, it oversimplifies by removing ourselves from the fleshliness of reality. I think we have purchased the concept that “the personal is political” wholesale without much interrogation on either side of the “is,” which unfortunately has gifted us this present moment that easily oversimplifies through words. Often, what is named is a personal set of infractions – “the personal” – as a means to speak about the uniqueness of one’s experience over and against the experiences of others, as a means to disrupt and shut down the possibility for interrogation. “The personal” is not about the capacity to be in the world with others but is, in effect, about the capacity to disengage in the service of personal, private protection from the world. It is antithetical to social justice because it disallows a conversation about structural inequity because the specificity of “the personal” as an example becomes the example par excellence. And “the personal” is often about the articulation of a set of infractions that makes of someone a victim, such that their sense of identity is grounded in such victimhood, and such victimhood becomes the shield against which no interrogation can occur. “The personal” is the elaboration of the bourgeois subject.

Then also on the other side of the “is,” is a need for interrogating “the political.” This concept is not neutral and has its own sets of problematics: political but towards what end? are we attempting to become the political subject of the state? If so, whatever is named as “the personal” used to articulate one’s capacity to be this subject of the state is, then, a problem that needs to be unsettled, disrupted. How Would You Feel is the articulation of “the personal” against which An Oversimplification of Her Beauty emerges as the interruptive force. The latter film refuses rapture, in its beautiful blackness, the film disbelieves in disengagement as the means to produce justice. It recognizes that rapture is not grounded in disbelief but a general disengagement from the fleshliness of our milieu.

v

There is something cool happening on subways in New York City. Kids are claiming space, expanding the possibility of movement, expanding – at the same time – the limits of imagination. There is something cool happening on subways in New York City. Gays are claiming space, expanding the possibility of movement, expanding – at the same time – the imagination for queer inhabitation, for queer livability. What makes the zone of the subway – a constrained, closed space on the move – the site from which emerges a critique of oversimplification? Why is this a zone from which to give an aesthetic intervention and interruption that misreads the normative ideologies of criminality for black young people in spaces where Stop and Frisk are normalized?

These various movements – while on the train on the move – are the critique of inertia, the movements of kinesthetic energy against potential and kinesthetic flesh, about striking a balance between movement and inhabitation. Theirs are movements on the move, movements that critique the ways of seeing them as potential criminals, potential threats to safety, potential enactors of violence. They utilize the confinement of subway cars to articulate other modes of being, they explode the potential energy of constraint through occupying the space with difference. They speak back, through performance, to how blackness, black flesh, is oversimplified and through such speaking back, fill the space with abundance, with excess, with ethical force. With each step, with each flip, with each pole dance, with each vogue, they not only articulate a disbelief in the conditions of the quotidian, they enunciate and elaborate the imagination towards otherwise possibilities. They pick up on Roy’s ethical charge, they ground themselves in Nina’s rhetorical dehiscence, they perform the doubleness of disbelief. They make, in other words, the world anew through a refusal of oversimplification of words.