i

We have been named from the outside, yet remain unknown. Needed for coherence, we have been disavowed for our fleshly capacity to derange normativity. We – us blacks and queers and women and trans* people and and and – are varied, many, intersecting varied modalities of identity. We – us that are not white, cis, heterosexual, male folks – come in many forms. We have been marked as marginal and discardable only after we arrived, marked from varied sides, from every whichaway. And this after our arrival only because rule and law exists insofar as it tries to correct an already existent unruliness. This unruliness is life, social life, life in and as blackness. Rules and laws are utilized to order the unruliness of the “us,” of the blacks and queers and women and trans* people and and and. Rules and laws “invent” as pathological our already existent mode of sociality as in need of control. Hoes and sissies and nappy hair in need of perms, rhetorically rehearse a more fundamental and foundational aversion to queer things, a queer mode of living that sets loose the very concept of blackness, because in such a concept is resistance that testifies to the power and force of gathering in the name and cause of something greater than the individual self. The individual self is a biological entity, a body, that can be counted.

But we live in a moment wherein the interrogation of the so-called naturalness of biology is necessary, wherein the social construction of the category needs be made explicit. Biology has never been on the side of the marginalized because the categorical mode of thought emerged from the same racialist projects that produced simple assertions about the purported simplemindedness of black folks. Biology has been used to pathologize; to on the one hand say that we simply are beholden to more primal urges and are thus unable to rise to the level of culture, while on the other it is used to explain away and justify things racism, patriarchy, sexism, homo- and transphobia. Think, for example, of the simplistic assertion that “men are visual creatures” … in such an assertion is a capitulation to sexual violence, is an assent to the notion that being “visual” is what disallows male-identified persons from acting justly because libidinal drives force them to look and to react with knee jerks and gazes and inequitable displays of power. The visuality of men, accepted as a biological – and thus, unavoidable – fact is the same sorta ideology that set loose not just the idea of racial difference but a hierarchy that says those who do not register visually as white are in need of constant correction and control through coercion. Visuality is but one register of such coercion. It occurs, likewise, in terms of how folks sound, how folks smell and feel, how folks taste. Biology, and really all of that which is called “science,” is harnessed in the service of patriarchy and no amount of appeals to it will do much good.

ii

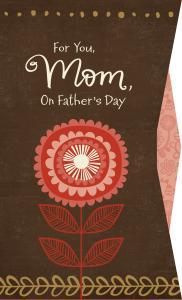

For Mom, On Father’s Day

Some of us have just celebrated, while others of us have lamented, Father’s Day in the United States. This day seems to bring out many emotions, and much of that emotive response is grounded in patriarchy and the purported need for a male-identified person to live “in the household” as proof positive of the proper development of children. It seems that a penis in the household becomes tantamount to a stabilizing presence, that the biologically male body serves as fortifying the unruliness and uncontrollability of the female flesh. The flesh of females, particularly and intensely the flesh of females that are likewise racialized black, register as that which is dangerous for biologically male and female children. We discovered this idea with Moynihan and his “report” that laid at the feet of black women the “tangle of pathology” of black social life. If a biological penis were in the household, then black social life would cohere with the wishes of the nation-state, reproducing the concept of the normative family, one that could be counted on to defend the nation, to be properly patriotic, to capitulate to the wishes of empire. The unruly biological black female mother has not the capacity within her to be a protector or provider, but merely functions as a presence of production. Black female flesh is proper for reproducing bodies for the furtherance of the goals of empire but certainly is not one that could provide something like stability in the lives of children. Such that black female flesh is constantly on display and desired for its capacities for production, though hypersexualized and discarded because of such hypersexualization.

So, many lamented the celebration of black women on Father’s Day, a day for folks with biological, and importantly not constructed, penises.This card seems to have offended people because according to many, “only men can be a father.” But what does this statement, and the sentiment behind it, actually mean? How have we arrived at a categorical distinction of what a father is supposed to be or mean or do that is not always and everywhere constructed by the milieu in which we live currently? If a father is one that protects, provides, cares for and is concerned with the concept of the family, how is that not reflected by the category we call “mother”? What, in theory and actuality, delineates the difference between such gendered roles? It all comes back to biology, how biology is utilized to not only make a claim for absolute difference but is used to then pathologize those of them, those of us, that do not abide by such strictures. Few of us, of course, do, but the aspiration towards such abiding is something to which we should attend in our intensely, explicitly neoliberal world. Rather than celebrating the fact that folks want to celebrate the important people in their lives, black female flesh, black mothers, were castigated for attempting to “play the role of the father,” because biology set the parameters for what is and is not possible for that categorical distinction. Biological distinction is, in other words, fuckin all of us up.

iii

Karlesha Thurman

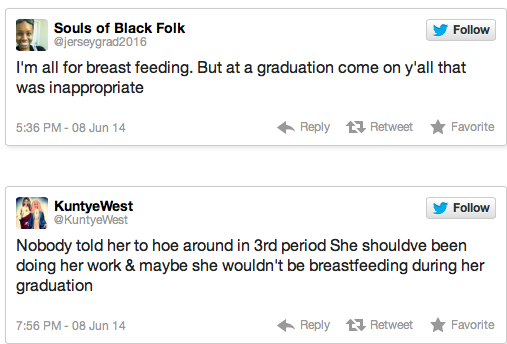

Graduating and celebrating all sorts of academic accomplishments, Karlesha Thurman was called a “hoe” because of her public breastfeeding of her child during her graduation ceremony.Because the set of assumptions about black female flesh as always unruly and out of order, sex and sexuality are always already moralized against. Many attempted to defend Karlesha – and rightfully so because folks that argued against her were simply silly – by saying that she was producing a biological act by breastfeeding, that what she was doing was grounded in science, not cultural practice nor a general cultural immorality. But such defenses only worked in the service of reifying the absolute difference and distinction between science on the one hand and culture on the other. Those defenses that turned to science – through biology – as the means that normalized her breastfeeding only ended up mining the very category of black female pathology in order to articulate why she, as individuated, should be given a pass.But such should not be the case. Why do we allow dudes to walk around beaches and streets and clubs without shirts but not women? Is it because there is something inherently different in the chests of men and women biologically? Is it because folks want to protect women’s flesh from being subject to gratuitous violence and violation? Not so. Not at all. Women are subject to violence – sexual and otherwise – not because of the unruliness of their flesh but because of the cultural collusion with science that produces something like patriarchal, sexist renderings of culture. Folks talked shit about Karlesha Thurman because not even biology offers recourse, because blackness and female flesh exist outside the bounds of biology.What is it about Karlesha Thurman’s “biological” condition that made her a “hoe”…? What is it that transforms something that is natural into something that is in need of being tamed, controlled, relaxed? It is the collusion of cultural with science that produces such a rendering of her feeding her child. And this collusion of science and culture needs much attention and interrogation.

Karlesha Thurman Comments

What we discover with Karlesha, and more emphatically with Blue Ivy Carter, is that there are two kinds of naturalness and, as such, two kinds of biological explanations for how folks exist in the world: that which is natural but in need of control and that which needs to be tamed; and that which should be cultivated, protected, proliferated, congratulated. Blue Ivy Carter has been the subject of hella scrutiny because of her hair, naturally grown out of her head though it may be.This particular photograph was such a problem that Blue Ivy became subject to a Change.org petition titled “Comb her hair”. The desire for her hair to be combed, to be otherwise than nappy – and both Crissle of The Read as well as Kimberly Foster at For Harriet have discussed this – is an affect of the naturalization of whiteness. But to move in their direction and further still, it is not just whiteness but the ways whiteness as biological is naturalized, how white bodies biologically are proper and that which falls beyond and aside the productions of white bodies are deemed problematic. Blue Ivy’s natural, biological hair is in need of taming, perming, combing, control. Her hair is not like other hair because, in effect, it is not white enough. Resorting to biological explanations for her hair simply won’t be enough because it is the unruliness of its blackness that is being interrogated, not any concept of so-called naturalness.

iv

The unruliness of Blue Ivy’s hair, the unruliness of Karlesha Thurman’s breastfeeding, the unruliness of celebrating flesh that doesn’t have biological penises for Father’s Day: they all mine an already existent pathology of black social life as in need of control, particularly through acts of violence. And this is true not just for the flesh of women-identified folks but for men and boys as well. There is pathology that is assumed to be true for black social life and only then, after such pathology is established as axiomatic, do various modes of categorical thought come to “explain” the reasons for unruly, queer, off, problematic behavior. And it is the afterlife of presumably true black pathology that Barack Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper Initiative (MBKI) coheres and builds its capacity for supposed change.

Blue Ivy Hair

MBIK is a program that seeks to help black and brown boys with self esteem, to give them mentorship, particularly by telling them they have “no excuses” and by telling their parents that they are the ones most implicated in the failings of their children. The initiative was created on the heels of George Zimmerman’s egregious acquittal and after the murder of Jordan Davis. Yet, instead of talking about structural and institutional racism, about the ways blackness is figured in the national imaginary as dangerous, as violent and as – yes – pathological, Obama chose rather an initiative that would set at the feet of the children so-attacked their issues in need of change. Obama ongoingly utilizes so-called black pathology as a means to identify with black American community: though his father was Kenyan and his mother white American, he uses the narrative of the absentee black father – one with much popular appeal, though not verifiable “scientifically” (funny how even science and math would disavow the very appeal he makes to it) – in order to identify with black American social life. But more than identify with it, he seeks to continually distance himself from such social life by declaring his success even though he purportedly shares conditions with the black folks he chides. Obama talks often with black folks about how his father was missing and how he smoked marijuana, and it is that lack and bad behavior supposedly gives him a foundation to talk about and to black folks in the States and their ongoing failings with respect to being impoverished, lacking education, having poor health and being constantly incarcerated.

Obama’s speech that inaugurated the MBKI intimated that he is exceptional because, unlike most black (and brown) boys, he had folks that cared about him and his well-being throughout the duration of his life. Such that his “bad behavior” did not impact him negatively in ways that it does others. This is not him speaking to privilege but him distancing himself from the black and brown boys that normatively do not have folks who love, care, nor respect them. Yet there have been folks organizing in the service of and love for black and brown kids for centuries, institutions from churches and mosques and schools to sororities and fraternities and social organizations.

The very foundation of the MBKI is founded upon a faulty idea that black and brown boys don’t feel care or concern from an early age. Yet research from educators like Janice Hale has demonstrated that black kids enter schoolsmore excited and ready to learn, achieve better and are more active than any other racial ethnic group, which is why Hale argues so much in favor of early childhood education. Black kids enter into schooling situations ready to learn even if, as Obama pointed out, they have a less extensive vocabulary than do white children at the same age. The problem is precisely that early on, black children feel the effects of institutional structural inequity: this happens through both microaggressive racialist practices and through more official means like testing and placing kids into remedial classes because they have “behavioral issues.” MBKI includes women through negation, through saying that the pathologies of black womanhood, of black motherhood, of black teaching women is simply not enough to control the behavior of black boys. What is needed is the controlling, stabilizing force of the black father, the black man.

However, the main problem with MBKI is not that it does not explicitly include women in its plan – it includes women through pathologizing mothering and teaching – but that the initiative itself is grounded in a general, nonspecific black pathology as axiomatic. It is grounded in the conceptual zone and frame that says blackness is unruliness and this unruliness must be controlled through varied forms of violent encounter with the nation-state. Sometimes, the violent encounter is with Stop-and-Frisk measures, with the increasing militarization of state police and general police and carceral practices. Other times, the violent encounter is with Race to the Top and its focus on “accountability” and “results” and “no excuses,” though schooling in general has been assaulted under the this current and previous administrations in the service of privateering profits. And at other times, the violent encounter is with initiatives that simply rehearse the language, logic and rubrics of neoliberal, individualist uplift narratives. MBKI is a science project, one that is founded upon the need to understand and, thus control, black pathology.

Like so many Blue Ivy strands of uncombed hair, like so many Karlesha Thurman breastfeedings, like so many sissies in sanctuaries, MBKI is a tactic of controlling the excesses of black social life. We should resist this with all of our being.

v

“These hoes ain’t loyal,” is but one sensationalist quotation from Jamal Harrison Bryant’s recent sermon titled, “I Am My Enemies (sic) Worst Nightmare.” In this sermon, he also decried the fact that the Black Church has created the condition wherein the only black men willing to abide there are “sanctified sissies.” He also discussed how there are “more lesbians” in the black community than ever before. This all because of the dissolution of the black family as a categorically distinct and pure zone, one that is relegated to father, mother and children. The failure for loyalty is felt everywhere and throughout the sermon: women aren’t loyal to men, gays aren’t loyal to holy libidinal drives, all to say that the failure of loyalty is a debt and personal moral failing, is an individualist infraction that is in need of reproving and adjustment. Bryant relies on the same supposed pathologies of unruly black sexualities that produced the conditions wherein Karlesha Thurman could be called a hoe: that something about her, about our, flesh is excessive to the point of danger for the whole of the community. It is the job of the excessive ones to regulate our behaviors for the salvation of the community. But this move for regulation and repression is to occur so we can fully, as a community, participate in the bounds of neoliberalism, not to disrupt and disfigure its function and form. Perhaps being disloyal to such aspirations is a gift. What worries Bryant, I think, is what worries Obama: the unruliness and uncontrolled nature of black sociality. Each participates, through various rhetorics and modalities, in the belief of an already believed, a priori black pathology that has to be both sought after and, after being found, destroyed.

And it is this search for the destroying of unruliness, of untamed hair and breasts and sexualites, that allows me to finally understand what Hortense Spillers means when she says that the black American male-identified person has the unique opportunity to “say ‘yes’ to the female within.” And must respond not to this opportunity, but to it as demand. What Bryant’s sermon demonstrates is a desire to tame the unruliness of queerness, the unruliness of female flesh, that is not grounded in the biological body but in the force of that which is deemed unruly, queer, excessive by the nation-state, by the inequitable distribution of power. Bryant wants to tame and perm and relax and control the aesthetics of the Black Church, of Blackpentecostalism, because in such aesthetic practice is the deformation of the very aspiration towards inclusion in national political initiatives that are only ever aspirations towards inclusion in neoliberal violence. Obama likewise wants to search for and destroy a similar unruliness. He participates in this search through Race to the Top measures, through initiatives that are supposed to “keep,” but that refuse to name emphatically systemic and instructional racism, sexism, homophobia, violence. They each tend towards the basic, pernicious ideology of blackness as offense, blackness as toxic and immoral.

What is needed is a general disbelief in the projects of empire, no matter how seductive the call for inclusion. A disbelief in the idea that what we are and already have is not enough. A disbelief in the pernicious and insidious ways pathologizing blackness operates in our moment. A disbelief in the capacity of empire to produce justice. A disbelief that nappy hair is bad, that breastfeeding in public insinuates acts of flagrant violence, that sissies in sanctuaries are not likewise vital for the quickening force of religious community. What is needed is a disbelief in the law of the father because the “law” is what establishes the very capacity to be a father, it normativizes certain relations as more important than others. But this has never been the truth for black folks, and I suspect others as well. Play aunties, play cousins, mom-moms, paw-paws, half-sisters, half-brothers, the people down the street and up the way: other socialities exist and cannot be reduced to or contained by the biologic necessity of blood. Biology restricts sociality and purports to be itself the grounds of culture. And it is this same law that incarcerates with racial and classed bias.

Yet, we can do and think and be otherwise. We can keep each other aside from, outside and beyond milquetoast federal initiatives. What is needed, in other words, is a disbelief in the current configuration of things that press both science and culture into the service of finding and critiquing blackness as deficit and detriment. This disbelief is the saying ‘yes’ to the radical force of black womanhood within.